Defining Games and Play

In their landmark 2004 game design textbook, Rules of Play, Salen & Zimmerman devote a chapter to definitions of games.

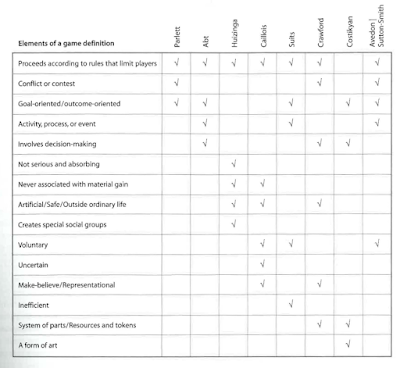

They run through eight definitions of games and play from various scholars—Huizinga, Caillois, Abt, Avedon & Sutton-Smith, Suits, Crawford, Costikyan, Parlett—and compare them in a single charming chart:

There are, obviously, many other definitions of games, but I think this chart does a pretty good job covering the basics.

That said, it is worth noting that Salen & Zimmerman do conflate play and games here; while they discuss those boundaries earlier in the chapter (Salen & Zimmerman 72–73), both Huizinga and Caillois primarily discuss play, rather than games. Granted, Caillois writes in French, where jouer, "to play," is simply the verb form of jeu, "games." But most translations of Man, Play, and Games—including Barash's, the one most people read—do decide to translate it as play. Huizinga, however, specifically calls attention to the games/play distinction at the very beginning of Homo Ludens (Huizinga 3), and as his own translator (for certain editions—it's a complicated history), is very intentionally choosing to use "play" over "game." The others all mention both games and play, but the definitions they offer primarily center on game, rather than play.

By conflating their definitions of play and games together in the chart, Salen & Zimmerman ignore some of the nuance: there are subtleties between a playful act outside the context of a game—say, rolling down a hill, or making puns, or flirting—and more formalized games. Those distinctions matter for us, as we'll see.

Because I'm a

noted fan, I'll also include De Koven's descriptions (not, interestingly, definitions) of game and play from

The Well-Played Game. On games:

For me, the oncept of games embraces those activities we know mostly clearly to be games—football, cat's cradle, gin rummy, peek-a-boo. These are clearly games.... I consider a game to be something that provides us with a common goal, the achievement of which has no bearing on anything that is outside the game. (De Koven xxiii)

And on play: "Play is the enactment of anything that is not real. Play is intended to be without consequence.... When we are playing, we are only playing. We do not mean anything else by it" (De Koven xxiv).

And finally, the now-common definition that Salen & Zimmerman themselves offer: "A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome" (Salen & Zimmerman 80).

Defining RPGs

In Role-Playing Game Studies: A Transmedia Approach, at the conclusion of Chapter 2, "Definitions of 'Role-Playing Games,'" Zagal & Deterding offer this accurate-if-unhelpful summary:

Many definitions of "role-play" and "role-playing games" have been suggested, but there is no rboad consensus. People disagree because they often have an unclear idea of what kind of phenomena they are talking about, and therefore, what kind of definition is appropriate.... Hence, if we ask for a definition of "role-playing games", we can only refere to either how particular groups at particular points in tiem empirically use the word and organize actions and the material world around it or how we, as a scientific observer, choose to use the word to foreground and understand a particular perspective... (Zagal & Deterding 47)

Worth noting that Zagal & Deterding here refer to RPGs a whole, including TTRPGs, larps, CRPGs, MMOs, and other myriad forms of roleplaying. The book does go into more definitions of TTRPGs in Chapter 4, but that chapter's authors—including

our good friend William J. White—don't manage to defeat the challenge that Zagal & Deterding describe.

The RPGs I discuss are the ones I play most often, which you're probably familiar with. Players take on the role of characters in a shared fictional world, and narrate their actions within that world. One player, the GM, doesn't have a single character they play, but instead plays "everything else:" NPCs, monsters, factions, the environment, and so on. Sometimes, the players or GM give up control over some aspect of the fictitious world and roll dice to determine how the game world operates.

They're RPGs. You're familiar.

My particular leaning is more sandbox-y, more open-ended, with fewer rules. "The OSR" has a lot of baggage as a term, but it's a reasonably good umbrella moniker for the style of play I enjoy and the games I run.

Most of the definitional work here applies to most categories of RPGs: traditional '80s-90s stuff, Forge-era storygames, Powered by the Apocalypse and its descendants, late-aughts retroclone OSR style, big crunch 4e grid games, newer-age NSR/FKR/etc OSR style, and so on. These definitions mostly don't apply to some of the most cutting-edge contemporary indie work: solo games, lyric games, and certain varieties of GMless game largely fall outside these definitions.

Onward!

Do We Play RPGs?

Yes! Yes? Yes. Almost certainly.

Huizinga defines play as an activity that is voluntary, nonserious, limited in time and space, ordered with rules, for its own sake, separate or distinct from reality, and featuring tension and joy (Huizinga 9–11). We'll talk about rules more in a bit, but RPGs are activities that are indeed voluntary, (infamously) limited, for their own sake, separate from reality, and feature tension and joy. Seriousness is an unclear element: Huizinga goes back and forth on the definitions of the term (Huizinga 5–6), but acknowledges himself that "Children's games, football, and chess are played in profound seriousness; the players have not the slightest inclination to laugh" (Huizinga 6). There's more to dig into regarding his definitions of seriousness (particularly as it pertains to ritual, culture, and the rest his book), but suffice to say Huizinga's definitions of play do not contradict the activity of an RPG. Checkmark from Huizinga.

Caillois largely agrees with Huizinga, defining play as free, separate, uncertain, unproductive in that creates no new goods or wealth, governed by rules, and make-believe in its awareness of a second reality (Caillois 9–10). Rules are, once again, the sticking point, but the other five certainly fit. Checkmark from Caillois.

De Koven's definition as enacting anything that isn't real (De Koven xxiv) fits RPGs perhaps better than almost anything else. Checkmark from Bernie.

Salen & Zimmerman's other six (as well as Salen & Zimmerman themselves) don't clearly define play in the separate way that Huizinga, Caillois, and De Koven do, so we'll leave them for the next section.

We'll get to the question of rules in its own section, which is a sticky point. But for now, we can say with some certainty that we do play RPGs.

Are RPGs Games?

Let's examine each of Salen & Zimmerman's fifteen comparative definitional points in turn (going in reverse order):

Art

Are RPGs art? Yes! There are inumerable definitions of art, but RPGs are expressive and creative. Good enough for me.

System of Parts/Tokens and Resources

The fuller line that Salen & Zimmerman pull this criterion from is this:

A game is a closed formal system that subjectively represents a subset of reality... By closed I mean that the game is complete and self-sufficient as a structure. The model world created by the game is internally complete; no reference need be made to agents outside of the game... By formal I mean only that the game has explicit rules... a game is a collection of part which interact with each other, often in complex ways. It is a system. (Crawford 4)

Do RPGs fit this? Not all of it. RPGs are fundamentally open: the rules are made to bend and change. Likewise, an RPG world is never "internally complete." As players take actions, they change the game world, altering the structure.

There is an argument to be made that the purely diegetic fictional world of an RPG does fit this definition, and that as players and GMs we merely examine one part of it: an argument that the world exists independently from our interactions, and that while we may never experience that world in its fulness, it is complete and self-sufficient.

That said, no text can fully contain such a world, and thus the published rules of an RPG certainly do not qualify.

As for Costikyan's definition, Salen & Zimmerman (seemingly) quote Costikyan in saying "A game is a form of art in which participants, termed players, make decisions in order to manage resources through game tokens in the pursuit of a goal" (Salen & Zimmerman 78). They cite Costikyan's famous text I Have No Words and I Must Design, but through a weblink, one that's now dead.

I've read I Have No Words and I Must Design, and I searched through my copy for that exact quotation, and I couldn't find it. I don't know where Salen & Zimmerman got that quotation from.

Do RPGs fit that definition? Not fully, no. Yes RPGs are art, yes they have players, yes those players make decisions, but only sometimes do they manage resources and only sometimes in pursuit of a goal. This may fit certain tables' games, but it's not a blanket yes.

(While we're on Costikyan, the definition of games from him that I learned in undergrad, which appears in I Have No Words and I Must Design, is as follows: "An interactive structure of endogenous meaning that requires players to struggle toward a goal" (Costikyan 25). An interactive structure of endogenous meaning does sound like an RPG, but one that requires players to struggle toward a goal certainly doesn't. Many RPGs have goals—get loot, gain levels, save the world—but at no point do the text, the GM, or the play processes demand players follow those goals, let alone struggle.)

Inefficient

Suits, in his rather wondrous book, The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia, somewhat idiosyncratically points out that games are deliberately inefficient: "...games are goal-directed activities in whihc inefficient means are intentionally chosen" (Suits 37). In poker, he points out, the goal is to win as much money as possible, but if you simply your opponents over the head, or if another player repays you a previous debt, you may've made more money—but you haven't won at poker (Suits 37). It's a fascinating observation.

Does it apply to RPGs? Yes and no. As

Mulligan points out, players—as they roleplay characters—seek the path of least resistance. RPG characters want to do things very efficiently: they don't want to struggle, they don't want to get hurt, they don't want to expend resources.

But players do want inefficient play. Walking into a dungeon, encountering no enemies, grabbing the loot, and then walking out entirely safely is unsatisfying. It's boring.

This once more gets into the question of the fictional world as game and the table as game.

Sidebar: Frame Theory. In the landmark RPG sociology book Shared Fantasy, Fine describes three basic frames, which are bundles of shared experiences, expectations, and identities (Fine 186, 194):

- The "primary framework," that is, the real world. Physical, actual reality, with all of its normal social rules and expectations. Players are themselves.

- The "game framework" formed from the rules and mechanics. Here, players are thinking in ludic game-mode: they make optimal, tactical decisions from within the context of the game and the rules.

- The "fictional framework," that is, the world of the game. Players are characters, fully inhabiting their fictional personas.

(For what it's worth, I think frame theory gets a lot of talk for what it is. It's a useful referential tool, perhaps, but in terms of both game studies and design, I find it a bit overblown.

The Dungeon Zone is fun, but it's a bit played out at this point. It also has a tendency to really draw the attention of my undergrad students to the point that they don't want to talk about anything else.)

I mention frames because they can cast some light with regards Suits and inefficiency.

Within the primary frame, as players and de-facto audience members, players want inefficiency. We want to struggle, to feel the tension, to, as Mulligan says, look back on a beautiful irrigated garden.

In both the game and fictional frame, however, players want to be as efficient as possible, and here a distinction emerges: in the game framework, inefficiency is indeed built in as Suits describes. Levels, feats, XP, stats—all increase over time but demand struggle and arbitrary requisites. A player may want to reach Level 20, but the inefficiency of the rules makes for a more satisfying experience.

In the fictional frame, however, there is no efficiency: all challenges are diegetic and inherent to the fictional world. We assume characters behave rationally and efficiently. When we encounter a monster in the dungeon, it's not because the characters want to encounter a monster, it's because the monster is really there. From within the fictional frame, if the adventure is satisfying, it is that way purely by happenstance.

So, are RPGs inefficient? Yes, but no.

Make-believe/Representational

Yes! Very obviously, RPGs are deeply ingrained in make believe, fantasy, imagination, and all related topics. When I say "I stab the monster," those words are a representation of a shared fantastical reality occurring elsewhere.

Uncertain

Yes! The outcomes of an RPG are deeply unclear, both in the dice's randomness but also in the raw uncertainty of multiple people contributing to a shared fantasy. Even without dice, RPGs are uncertain because reality is uncertain.

Voluntary

Yes! If you don't want to play an RPG, you aren't. A player can stand up and walk away from the table. Indeed, if players don't agree to the balance of narrative authority—between the players, the GM, and any other elements at play—the game falls apart.

Creates special social groups

Yes! See Fine, Shared Fantasy. Or indeed nearly any depiction of RPG players from the past 50 years.

Artificial/Safe/Outside ordinary life

Huizinga writes that "...play is not 'ordinary' or 'real' life. It is rather a stepping out of 'real' life into a temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own" (Huizinga 8). He goes on to say "What the 'others' do 'outside' is no concern of ours at the moment. Inside the circle of the game the laws and customs of ordinary life no longer count. We are different and do things differently" (Huizinga 12).

Caillois writes that play is "Separate: circumscribed within limits of space and time, defined and fixed in advance" (Caillois 9).

Crawford writes "A game, then, is an artifice for providing experiences of conflict and danger while excluding their physical realizations. In short, a game is a safe way to experience reality" (Crawford 12).

De Koven writes:

Play is the enactment of anything that is not for real. Play is intended to be without consequence. We can play fight, and nobody gets hurt. We can play, in fact, with anything—ideas, emotions, challenges, principles. We can play with fear, getting as close as possible to sheer terror, without ever being really afraid. We can play with being other than we are—being famous, being mean, being a role, being a world. When we are playing, we are only playing. We do not mean anything else by it. (De Koven xxiv)

On its face, RPGs seem to neatly fit these definitions. RPGs take place in a fictional world, as fictional characters. Players regularly play characters who murder and steal, and everyone has a good time.

On the other hand, there's bleed. Role-Playing Game Studies defines bleed as "the phenomenon when a player's thoughts and emotions influences the thoughts and emotions of the character they are role-playing (bleed-in) or a character's thoughts and emotions influence the player (bleed-out)" (Stenros, Bowman, et al. 420).

Bleed is everywhere. We constantly feel emotions as a result of our characters' feelings, and our characters constantly act under the emotions we feel. This is a large part of why safety tools are important: they provide structured ways to stop or slow unwanted emotions at the table.

To a certain extent, the existence of bleed proves that RPGs are not separate from real life. The sheer fact that safety tools exist is an argument for the connection between reality and play.

While bleed perhaps contradict's Crawford's and De Koven's definitions, it doesn't preclude Huizinga or Caillois' definitions. RPGs are indeed distinct: we all meet at a certain time and we sit around at a certain time.

While bleed poses some emotional threat or danger to players, it is still incomparable to the physical dangers that the characters face. When a monster kills a character, the player does not die.

So are games artificial or separate or safe? Yes, but no.

Never associated with material gain

Yes! While there were a few RPG tournaments in the '80s, they never caught on. There is no comparable play within RPGs to anything like professional sports, gambling, or large-scale tournaments.

(There is a separate argument here regarding the shift from GM to game designer selling their work as a monetization of the hobby, but game design itself is fundamentally distinct from play.)

Not serious and absorbing

As mentioned before, Huizinga is a bit contradictory on this. I think Salen & Zimmerman's depiction is overly simplistic. RPGs certainly are serious and absorbing, but it's not clear according to Huizinga what bearing this has with regards to an activity's status as play.

Involves decision-making

Yes! Many decisions are made in RPGs at all levels of play.

Activity, process, or event

Yes! RPGs are clearly an activity. You play RPGs.

Goal-oriented/outcome-oriented

Most RPGs do not have explicit goals or outcomes in the traditional sense. In very few RPGs can you "win" or "lose."

Indeed, Salen & Zimmerman go on to point out RPGs as an exception to their own definitions: "Role-playing games clearly emobdy every component of our definition of game, except one: a quantifiable outcome... In other words, there is no single goal toward which all players strive during a role-playing game" (Salen & Zimmerman 81). They equivocate on this a bit by saying that individual sessions may have goals—kill the dragon, save the king, steal the hoard, etc.—which can form outcomes (Salen & Zimmerman 82).

I think their analysis is largely accurate. There are lots of small goals in RPGs from session to session, but there is no overarching goal. Likewise, in most RPGs, those goals are extremely player-defined: there is no requirement or task set by the game that the players must follow. While there may be fictional incentives towards certain goals (kill the dragon so it doesn't destroy the town) and certain non-fictional player goals (a player wants to have an in-character romance), neither of those are strictly binding, and neither are required for an RPG to function.

On the other hand, within the primary frame, there are many goals: players want to tell an exciting story. They want to feel cool and powerful. They want to explore another world. They want to have a good time with friends. But these primary frame goals are not unique to RPGs, nor even to other games: a player may want to have a fun time with chess, but "have fun" is not a rule of chess.

Are RPGs goal- or outcome-oriented? No.

Conflict or contest

To some extent, the answer is an obvious yes: there are dragons to be slain and treasures stolen. The basic ability check is fundamentally a form of conflict.

There are three counterarguments to this. First, in most RPGs, the mechanics that allow these contests to occur are simulated: a Strength check is a check to see if a character can lift something heavy. What that lends itself to varies: it could be a check to swing the sword that slays the dragon, or it could be a check to lift a weight on a squat rack. A check is based on uncertainty, but that uncertainty does not necessarily require conflict or contest.

One possible exception to this is that of conflict vs. task resolution, as defined by Baker in "Roleplaying Theory, Hardcore." Baker writes:

Task resolution is succeed/fail. Conflict resolution is win/lose. You can succeed but lose, fail but win.

In conventional rpgs, success=winning and failure=losing only provided the GM constantly maintains that relationship - by (eg) making the safe contain the relevant piece of information after you've cracked it. It's possible and common for a GM to break the relationship instead, turning a string of successes into a loss, or a failure at a key moment into a win anyway.

...whether you succeed or fail, the GM's the one who actually resolves the conflict. The dice don't, the rules don't; you're depending on the GM's mood and your relationship and all those unreliable social things the rules are supposed to even out.

Task resolution, in short, puts the GM in a position of priviledged authorship. Task resolution will undermine your collaboration. (Baker "Conflict Resolution vs. Task Resolution")

Under these parameters, Baker describes altering the otherwise-simulated nature of common RPG resolution mechanics into mechanics that instead fundamentally alter the shared fantasy. The role of the dice shifts to a more oracular role: they determine not only performance or ability but the nature of the fictional world. A check would only be made, in these contexts, when there is necessary conflict that demands resolution. It's important to note that these ideas, as written in the text, only apply to some RPGs. A GM could perhaps alter another RPG's text to better fulfill Baker's ideas, but not all RPGs behave this way.

The second issue, however, one that even Baker's framework does not resolve, is that at no point does an RPG necessarily demand conflict within its fictional world. It's entirely possible to play an RPG and simply never encounter anything dangerous or uncertain—that's not how most tables play, but there's nothing stopping those tables from doing so.

The third counter to the claims that RPGs are based on contest is that players and GMs are not strictly in competition with each other. There are cooperative games, certainly, but the lack of any clear goal in an RPG means that players are not working against some opposing force. There are moments of conflict that occur as a result of the fiction, but those are not required or enforced by the RPG in and of itself.

Do RPGs feature (necessarily) conflict or contest? No.

Proceeds according to rules that limit players

Consider Fine's frames again: where do the rules exist?

In the primary framework, we have rules regarding our conduct at the table, most of which are not codified by the text: listen when somebody talks. Show up on time. Don't throw your dice at other players. (It's worth noting that a few RPGs, like Avery's The Quiet Year, do interact with this framework: in The Quiet Year, players may only speak at a certain time. These RPGs are unusual, though, and are outside much of the discussion thus far.)

In the game framework, we have many, many rules: ability checks, attack rolls, saving throws, class, species, class, level, HP, and so on. These rules are strictly governed by the text.

In the fictional framework, the rules vary. Some of them are rules of the fictional world as defined by its inhabitants ("in this city, weapons are not allowed"), and thus can be broken like laws. Some of them are implied by our own world's rules, like physics ("if you don't eat, you will starve"). Some of them are unique to the fictional world ("when the moon is full, you transform into a wolf").

In most RPGs, the game framework and fictional framework interact regularly. If you transform into a wolf, your game statistics change to match the wolf. This is common in most kinds of games.

In his unfinished manuscript, Inventing the Adventure Game, Robinett writes:

Making a simulation is a process of abstracting -- of selecting which entities and which properties from a complex real phenomena to use in the simulation program. For example, to simulate a bouncing ball, the ball's position is important but its melting point probably isn't. Any model has limitations, and is not a complete representation of reality. (Robinett, Chapter 5, "Getting Ideas")

In an RPG, the rules too are abstractions, and those rules may simulate the ball's position. What is unique to RPGs, however, is that despite not existing in the rules, the ball still has a melting point. Just because an element of the world is not present in the abstract simulation of the rules does not mean that element does not exist.

In RPGs, the fictional framework takes precedence, regardless of abstraction: if a character transforms into a wolf and their statistics don't change, it feels strange. It feels incongruous, or cheap, or fake. We expect the rules of the RPG to conform to the fiction.

Likewise, in most RPGs, characters are not limited to what the rules explicitly allow them to do, but instead to behave how they choose within the fictional context of the world. Zagal & Deterding write that in RPGs, "Attempted character actions are limited only by the imagination of controlling players" (Zagal & Deterding 45). A character may attempt nearly anything. They may not succeed—at most tables, a character could not jump to the moon—but they may try.

Because of this reversed relationship, that the rules of the game framework are dependent on the rules of the fictional framework, the written rules of the text diminish in importance. It is possible to play an RPG with no game framework—the primary and fictional frames must exist, but the game frame is secondary. Abstractions are purely representational: the map is not the territory.

All that said, the primary and fictional frames do still present rules that must be followed. If players can't agree to the basic conventions of their group, or if start breaking the rules of the shared fictional reality, play stops. Critically, in most RPGs, the rules of the primary frame are left entirely unspoken, and in many RPGs, the rules of the fictional frame are meant to be changed or expanded upon.

So, do RPGs proceed according to rules that limit players? Yes, but the rules necessary to play are not those found in RPG books.

In Summary

Here's the checklist in order:

- Proceeds according to rules that limit players: Yes, but not the rules found in the text.

- Conflict or contest: No.

- Goal-oriented/outcome-oriented: No.

- Activity, process, or event: Yes.

- Involves decision-making: Yes.

- Not serious or absorbing: No, but this is hard to define.

- Never associated with material gain: Yes.

- Artificial/Safe/Outside ordinary life: Yes, but no.

- Creates special social groups: Yes.

- Voluntary: Yes.

- Uncertain: Yes.

- Make-believe/Representational: Yes.

- Inefficient: Yes, but no.

- System of parts/Resources and tokens: No.

- A form of art: Yes!

Obviously, Salen & Zimmerman provide these comparisons to demonstrate there is no one singular definition of game. It is an old and ongoing debate within game studies.

But it's clear that RPGs defy much of what makes normal games what they are. They aren't like normal games. They don't work in the same way. Videogames, board games, card games, folk games, party games, sports—there is a great of overlap between them, and relatively little overlap with RPGs.

RPGs are unique.

Conclusion

Consider De Koven's definition once more: "...something that provides us with a common goal, the achievement of which has no bearing on anything that is outside the game" (De Koven xxiii). Once again, the answer is contradictory. Within the rules of the text or the context of the fictional world, no, RPGs are not games. But as players, as people who want to play, then yes, of course RPGs are games.

So what does this mean? What does RPGs' status as weird fringe maybe-games tell us?

The most obvious conclusion is that, within the pedagogy of game design, the design skills between RPGs and most other games are significantly less transferable than between other types of games. If you're trying to learn or teach RPGs, you need to do it differently than the other games.

The other conclusion, particularly with regards to the definitions surrounding rules, conflicts, and goals, is that a lot of what gets put into RPG books largely doesn't matter. The elements that change the fictional world—setting, genre, adventure, tone, aesthetic—do exist in many RPGs, but they are rarely given the same foregrounding as the rules.

As designers, the key question we need to ask ourselves at every turn is this: are rules the most effective way to get the outcome we want? Game design is, to a large extent, the design of experiences. But because rules have relatively little importance compared to other games, it's worth strongly considering how much of what you want players to experience is defined by the rules. In terms of what is actually played at the table, rules are often secondary in impact compared to non-mechanical writing. Defining the world in fictional terms has a much stronger impact than defining it in rules.

So go forth and design, in the knowledge that RPGs are weird and the rules don't matter.

Works Cited

Baker, Vincent. "Roleplaying Theory, Hardcore."

Caillois, Roger, trans. Meyer Barash. Man, Play, and Games.

Costikyan, Greg. I Have No Words and I Must Design.

Crawford, Chris. The Art of Computer Game Design.

De Koven, Bernard. The Well-Played Game.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens.

Salen, Katie, and Zimmerman, Eric. Rules of Play.

Suits, Bernard. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia.

Zagal, José, and Deterding, Sebastian. Role-Playing Game Studies: A Transmedia Approach.